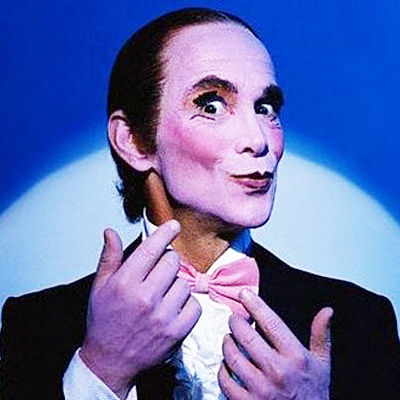

Joel Grey as the MC in Cabaret.

I saw a new self through a glass, brightly lit by naked bulbs, during the make-up workshop at the National Theatre. Be (true to) yourself, people say, and it’s good advice, with reservations. You have to accept that yourself might be sadistic, cowardly or weak, at times, but the thing is, it’s also not clear to which self they’re referring, let alone how it’s to be discerned. As Charlie Runkle replies, when told to be himself in an episode of Californication, “…and, who would that be, again?”

Make-up was familiar to me, and dressing rooms, as was the adoption of characters. At the workshop, they made us put on full stage make-up. It was a lesson in the basic technicalities of highlighting a face, making its expression more visible at a distance. Because I never was good with fine motor work, as I followed the instructions, what emerged was a fabulous drag-queen facial regalia – rouge, lippy, liner, mascara, highlights, the whole bit. No frock, just the loose clothes we worked in. I didn’t need one. My whole demeanour changed.

They didn’t ask us to adopt characters. They didn’t need to. I could have done a show at Trish’s, the legendary drag bar in Carlton. My stride became longer, my hips looser. I held my hands near my shoulders, touched people more frequently, and easily, and they didn’t seem to mind. I didn’t will any of this. It just happened, when I looked in the mirror and saw this dahling version of myself.

Dressing rooms are magical, everybody knows that. I could already slip into a character like throwing on a chiffon negligee. I could give you a New York accent that once, I’m proud to say, actually convinced a New Yorker. (Several, in fact. One of them showed me off to another. ‘He got the R’s right’, the other grudgingly allowed. I’ve always taken this as high praise from a Manhattanite.) But, although I was more of a ‘just do it’ kinda player, I went along to the National Theatre – the Actors Studio of Melbourne – three nights a week for three hours, for nearly a year. Hey, I won it as a prize scholarship. I never was good at set-piece auditions, but this landed in my lap.

Dressing rooms are magical, but not like the moment of becoming visible, of stepping from backstage to onstage, or when the lights come up or the curtains open. I wrote a poem about it once. That was at the New Theatre, in North Carlton, where the Trots and the Leninskis tried to come to terms with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of their dreams. I wrote skits for their end-of-year review (the New World Odour), and played the explorer John Eyre in a play called Dead Heart. For revolutionaries, many of them were curiously passionless, and for communists, they had a strong sense of ownership, especially of beer at parties. This was a severe blow to my normal approach to partying – drinking other people’s booze and being passionate about stuff. These were the younger ones, shockingly. The older ones were different, and would argue the point about the Provisional Government and reminisce about the Vietnam Moratoriums before warming up their voices with impressive renditions of The Red Flag. Some of them remembered plotting revolution in the ’30s, in the coffee shops of Swanston Street, when it all seemed possible, the continuation clearly discernible – imminent – and they hadn’t heard about the purges.

When they’re in mobs, you have a totally different relationship with them. The mob moves like a single thing. It laughs at your jokes, falls into hush at emotional moments. Who are you, then? Who are they? It’s not you they like, or are amused or moved by. Or is it? Hazy and indistinct, somewhere in the connection, you are discernible in the character, and they can see themselves. They’re combined into a single thing through this attention, and the group thing is as unique and ephemeral as a person, manipulable as a mob of cattle. When you think ‘human nature’ remember the mob, which is as much a part of individuals as individuals are part of it.

I used to love the way that time progressed through a play. You do one scene, then another, then someone else does one and you wait. You strut and fret, each moment moving into another, and then it’s over, and you’re you again. The makeup comes off. That particular audience dissolves. Then you do it again the following night. During the sequence, the time progresses so precisely it becomes salient as a part of the thing: the play, in four dimensions, makes space-time comprehensible.

I discovered at nine that I could make people laugh, and found I could relate to people en masse in ways that were somehow both detached and incredibly intimate. The chiffon negligee is translucent: even as it changes the silhouette and transforms the light in unexpected ways, and makes an illusion so convincing even its inhabitant almost believes, the reality underneath is still there, shadowy, visible but vague. The best actors are ultimately personally vulnerable without, somehow, ever really exposing themselves. Stepping into the light is also stepping into someone else, confidently, safely indistinct.

I had special paint on my shell costume when I was a barnacle in the Alpha Children’s Theatre’s production of A Mermaid’s Tale, so when the UV lights came on, I glowed in the dark. Make up on the costume, a shell that altered my silhouette completely, to something a bit like the ladies’ room sign. I said things and hundreds of people laughed. Or at least, The Barnacle said things. I’m not quite sure who it was. Later I was a hit as a lion. In the theatre, you can be a lot of things. You can be free, as long you’re disciplined and meticulous, and follow a rigid set of rules of the form. You can be timeless, as long as you keep strictly to your cues. You can be someone else, but the danger is losing sight of yourself. I still fall into the drag persona, not always intentionally or appropriately, but easily. We move through space and time: diaphanous me, and my magical dressing room.